Hans Thøger Winther, 1786-1851. Fotografisk opfinder, jurist, bogtrykker, boghandler

Hans Thøger Winther var født i Thisted i Jylland.

|

An album description from this page: HER

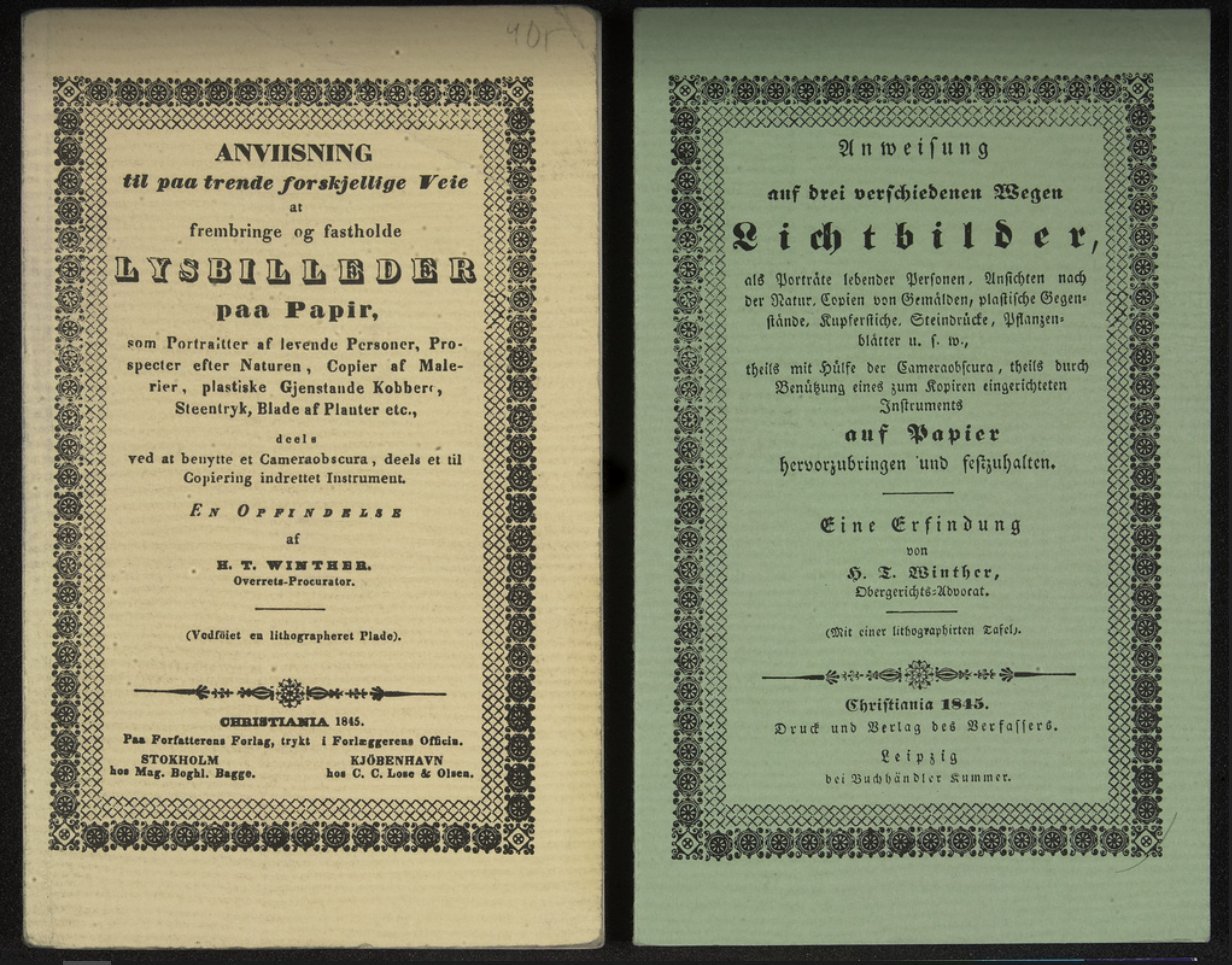

Direct Positive, reversal process published in Norway in 1845 by the author, publisher, printer Hans Thøger Winther (1786-1851) in Christiania (Oslo). He published his three principal photographic inventions developed in the period 1839-1843 in a small book, one in Norwegian and parallel to this one in German, both printed in his publishing house in Christiania (Oslo) 1845. His photographic heritage has been lost except for three images rediscovered a few years ago preserved in The Herman Krone Samlung in Dresden, Germany. Tak til Rudi Hass, som har ført mig på sporet af denne historie. |

The Winther's

Bichro-Silver process he developed in August 1842 is based on two

principles. No. 1 the highlights are created by exposure of paper in the

camera without any silver halides present, only the Potassium

Dichromate coating (hence the long exposure times). No. 2 the shadows

are created after washing and drying the dichromate mask by exposure to

direct sun/daylight after Sliver Chloride is formed on the paper

surface, as in salted paper. Later, after curing, the hypo takes care of

the unexposed silver while Nitric Acid (can be avoided) clears the

Dichromate off the highlights leaving white paper there. It is quite

ingenuous and different from any other early positive processes but

exposure times are long, usually demanding an hour in full sun in the

summer. The resulting images are unique and like daguerreotypes are

reversed.

|

|

"Smaaskrifter af praktisk-naturvidenskabeligt Indhold" skriver Munch-petersen i Dansk Biografisk Leksikon, men netop dem bliver han "husket" for i dag. Han var fotopioner - fandt en metode til at frembringe "lysbilleder" på papir, men er i dag nærmest helt glemt. Reprint 1989. Om danskfødte H. T. Winthers opfindelse af den fotografiske proces, Christiania 1845. En konkurrent til Daguerre! 52 sider. Heftet. Planche med tegning af hans kamera.

|

Dette er den første boka om fotografi som kom ut i Norge. Den kom ut i 1845 og beskriver Hans Thøger Winthers egen metode " til paa trende forskjellige Veie at frembringe og fastholde Lysbilleder paa Papir".Den beskriver hans prosess og gir oppskrifter på kjemikalier og tegning av kamerautstyr. Finnes på norsk og tysk

|

|

Winther, Hans Thøger, 1786-1851, Jurist og Forfatter, var født i Thisted 22. Jan. 1786, men kom 1801 til Christiania, hvor han 1806 tog den juridiske Examen («i Modersmaalet») og 1808 blev Sagfører. 1822 etablerede han en Boghandel og oprettede 1826 et Bogtrykkeri. Han var gift med Cathrine Marie Gundersen, Datter af Kjøbmand Even G. i Christiania. Han døde 11. Febr. 1851.

Foruden nogle Smaaskrifter af praktisk-naturvidenskabeligt Indhold har han udgivet flere populære juridiske Skrifter, saaledes navnlig under Psevdonymet «Hans Holst» en «Juridisk Haandbog for den norske Landalmue», der kom i en Mængde Oplag. Desuden udfoldede han en flittig Virksomhed som Udgiver af populære Tidsskrifter som «Bien» (1832-38), «Ny Hermoder» (1841-43) og «Arkiv for Læsning» eller «Norsk Penningmagasin», til hvilke han ogsaa leverede flere Bidrag i Poesi og Prosa. Kraft og Lange, Norsk Forf. Lex. H. Munch-Petersen. |

Winthers tre fototeknikker som ble utviklet i årene 1839-42 ble møtt med beskjeden interesse til tross for annonsering både i Norge og i utlandet. I dag hører hans navn til en eksklusiv liten gruppe pionerer, såkalte «protofotografer»,og han regnes samtidig som den norske illustrerte pressens far.

Her i Norge har man ikke klart å spore opp noen av hans egne fotografier, og kun tre fotografier er funnet i Tyskland. Til tross for dette store savnet gjør Winthers bok: Anviisning til paa trende forskjellige Veie at frembringe og fastholde Lysbilleder paa Papir (1845) det mulig å følge oppskriftene for å undersøke om de faktisk var brukbare. Wlodek Witek Se siden HER. Og læs om fotograf Wlodek Witek HER |

Hans Thøger Winther. Selvportræt (?)

|

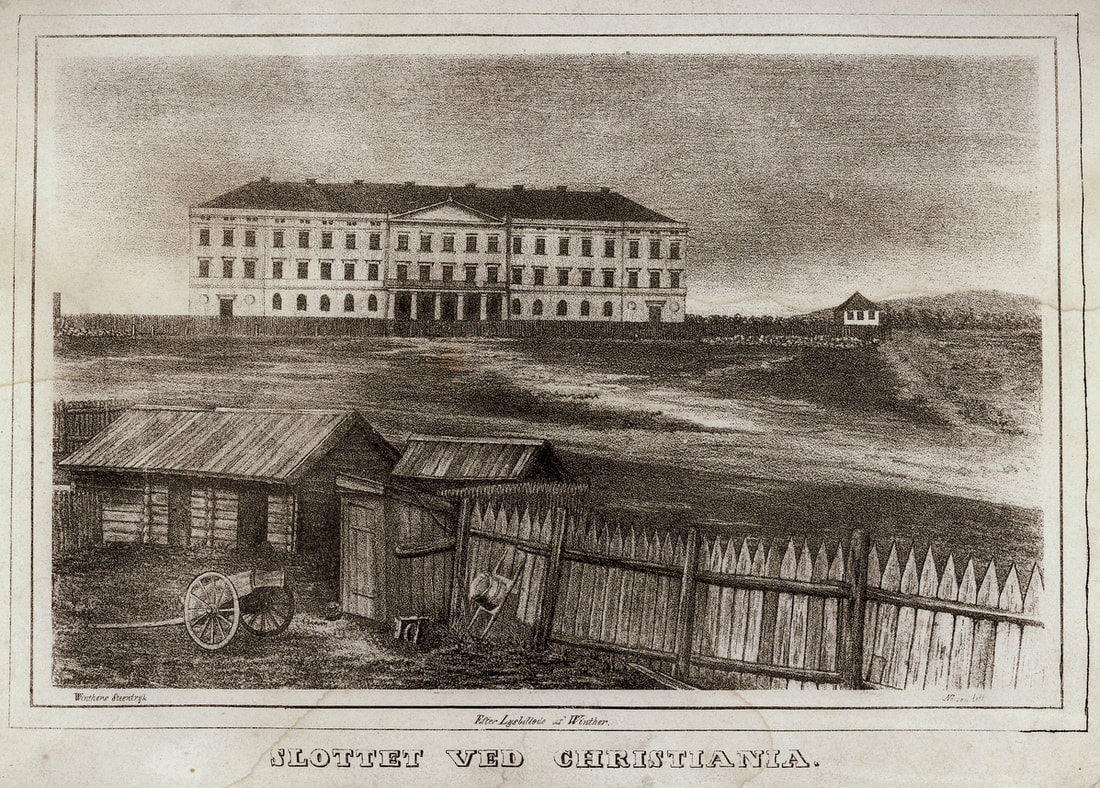

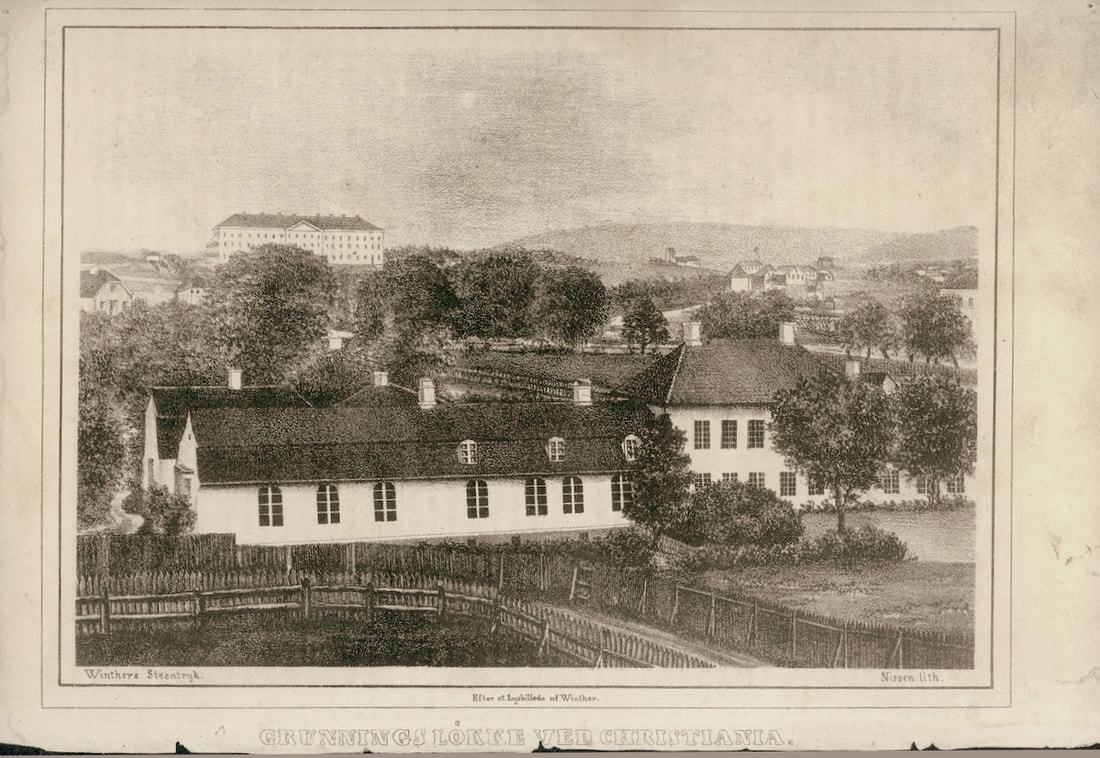

"Slottet ved Christiania" ("The Royal Castle near Christiania"), published June 1, 1843. Efter Lystryk af Hans Thøger Winther. Oslo Museum. Til højre må det være et af hans originale arbejder, "gadeparti i Christania", formentlig et af de tre, man har fundet i Herman Krone Samlung i Dresden, Tyskland.

For Winther var fotograferingen en hobby, han åpnet aldri noe atelier. Han eksperimenterte med fotografi og fant frem til tre prosesser, en direkte positiv, en negativ/positiv og en diapositiv. Den siste fortjener han all mulig ære for, ettersom den baserer seg på en kjemisk effekt som ingen andre kjente til, eller nyttiggjorde seg innen fotografi. Winther regnes til en av de mer interessante sub-oppfinnerne av fotografi, d.v.s. blant dem som egenhendig klarte å finne frem til egne originale prosesser før 19. august 1839 men etter 7. januar 1839. Det betyr at de hadde hørt om Daguerres oppdagelser uten å kjenne til detaljene. Således fremstillet han allerede i 1839 direkte positive bilder på papir. I 1842 var han gått over til å bruke papirnegativer. Han må sannsynligvis regnes som Norges første fotograf. (Kilde lokalhistoriewiki.no og Preus Museum).)

For Winther var fotograferingen en hobby, han åpnet aldri noe atelier. Han eksperimenterte med fotografi og fant frem til tre prosesser, en direkte positiv, en negativ/positiv og en diapositiv. Den siste fortjener han all mulig ære for, ettersom den baserer seg på en kjemisk effekt som ingen andre kjente til, eller nyttiggjorde seg innen fotografi. Winther regnes til en av de mer interessante sub-oppfinnerne av fotografi, d.v.s. blant dem som egenhendig klarte å finne frem til egne originale prosesser før 19. august 1839 men etter 7. januar 1839. Det betyr at de hadde hørt om Daguerres oppdagelser uten å kjenne til detaljene. Således fremstillet han allerede i 1839 direkte positive bilder på papir. I 1842 var han gått over til å bruke papirnegativer. Han må sannsynligvis regnes som Norges første fotograf. (Kilde lokalhistoriewiki.no og Preus Museum).)

"Grunnings Løkke ved Christiania" ("Crunning's Carden near Christiania"), published April 8, 1843; "Efter Lysbillede af Winther", Oslo Museum.

"Kongens Gade i Christiania" ("The Kings Street in Christiania"), published May 10, 1843; "Efter Lysbillede af Winther", Oslo Museum.

"Frimurerlogen i Christiania" ("The Freemasonry Temple in Christiania"), published February 21, 1843; efter lystryk af Winther. Oslo Museum.

Hans Thøger Winther, 1786-1854

|

Bokhandler, boktrykker og fotografipioner. Foreldre: Konsumpsjonsforvalter Thomas Nicolay Winther (ca. 1745–1808) og Mette Marie Müller (1766–1811). Gift 4.5.1809 i Christiania med Cathrine Marie Gundersen (25.4.1792–25.3.1879), datter av kjøpmann Even Gundersen (1760–1807) og Anne Marie Gundersdatter Brandvold (1766–1806).

Hans Thøger Winther var født i Danmark, men fikk sitt virke i Norge, som bokhandler, forlegger og boktrykker. Han er i ettertid særlig kjent som pioner innenfor fotokunsten. Winther kom til Christiania 1801 som kontorist hos den senere eidsvollsmann og høyesterettsassessor Christopher F. Omsen. 1806 tok han juridisk embetseksamen og ble sakfører, først i Akershus amt, så ved Akershus stiftsoverrett, og 1815 ved samtlige over- og underretter i landet. Etter hvert bygde Winther opp en omfattende virksomhet som hadde lite med jus å gjøre. 1822 åpnet han en bok- og musikkhandel i sitt eget hus på hjørnet av Østre gade (senere Karl Johans gate) og Øvre Slotsgade. Kundene måtte gå gjennom hagen, opp en bakke og så opp en trapp til annen etasje. Sent 1826 monterte han egen presse med steintrykkeri i kjelleren, og året etter begynte han også forlagsvirksomhet. Den litografiske trykkmetoden var oppfunnet mot slutten av 1700-tallet. To tyske litografer, Louis Fehr og sønnen Gottlieb, hadde åpnet en litografisk anstalt i Christiania 1822, men Winther fikk større betydning, med en omfattende og variert billedproduksjon. Han utgav portretter av kjente nordmenn, landskaper og byprospekter og litografier av grunnloven. Et stort prospekt av Christiania 1835 gir et utmerket bilde av byen og en rekke viktige bygninger. P. T. Malling var i flere år faktor hos Winther. I Norge var det få tidsskrifter før 1800. Winther begynte å utgi et firesiders ukentlig blad, Anmeldelser, Literatur og Kunst vedkommende, 1827–29. Deretter kom bl.a. Bien. Et Maanedsskrift for Moerskabslæsning 1832–38. Det ble populært rundt om i landet, men mangelfull samferdsel gjorde distribusjonen vanskelig. 1839–40 kom Norske Læsefrugter, som gikk over til Ny Hermoder. Et esthetisk Ugeskrift 1841–43. I flere av bladene skrev Winther selv dikt, biografier, historiske skisser og fortellinger. Hans viktigste tiltak var det som kort etter starten fikk navnet Norsk Penning-Magazin, et Skrift til Oplysning, Underholdning og nyttige Kundskabers Udbredelse 1834–42. Som supplement til dette månedsskriftet, som kom med hefter på 128 sider, nådde Winthers steintrykk frem til et stort publikum. Interessen ble ikke mindre da det dukket opp en konkurrent, Skilling-Magazin, som flyttet billedstoffet inn i teksten og dermed representerte starten på den illustrerte underholdningspressen i Norge. Winthers bokforlagsvirksomhet ble innledet med et skuespill av H. A. Bjerregaard, Clara. Senere kom skjønnlitteratur, skolebøker, religiøse skrifter, en illustrert bibel og praktiske småtrykk, bl.a. veiledning i å brenne brennevin, brygge øl og lage engelsk skosverte. Blant skjønnlitterære forfattere kan nevnes Henrik Wergeland og Walter Scott. Wergeland var også medarbeider i Penning-Magazin, der flere av hans fineste dikt ble trykt, og han fikk publisert sin lille verdenshistorie og den anonyme Sveriges historie. |

1825 opprettet Winther et leiebibliotek – ikke helt uvanlig blant bokhandlere på denne tiden – med 400 bind og like mange notetrykk. Til tider kunne hans virksomhet bli så mangfoldig og vekslende at han hadde problemer med å holde styr på det hele. Flere av hans tiltak fikk kort varighet, mens andre ikke ble satt ut i livet. Subskripsjonsplaner ble lagt til side fordi det ikke meldte seg mange nok interesserte. En del konkurrenter så på ham med ublide øyne. Han var velstående og drev enkelte deler av forretningen bare fordi han hadde glede av det. Han kunne dyrke kunst og musikk og hadde omgang med ledende kunstnere. Halfdan Kjerulf var en av hans venner.

Winther utviklet flere metoder til fotografisk gjengivelse og utgav 1845 landets første fotobok, Anviisning til paa trende forskjellige Veie at frembringe og fastholde Lysbilleder paa Papir. Det var en av verdens tidligste bøker på dette området, men arbeidet fikk mindre betydning, siden andre metoder, daguerreotypi og kalotypi, ble grunnlag for utviklingen videre. Gradvis trakk Winther seg ut av sin virksomhet. En av hans sønner, Edvard, overtok den lithografiske anstalten 1841, og drev den til 1878. Sønnen var teologisk kandidat, og arbeidet også som kopist i Kirkedepartementet. En annen sønn, Wiktor Julius, gikk i boktrykkerlære hos faren, var i ung alder en kort tid faktor og flyttet så til Tønsberg, der han 1839 startet byens første trykkeri, men allerede året etter utvandret han til Tyskland. Etter at Winther døde, giftet hans datter seg med bokhandler Joh. Chr. Hoppe, som kjøpte eiendommen i Øvre Slottsgate, fikk den revet og oppførte en ny bygning, som 1854 ble overtatt av boktrykker W. C. Fabritius. Verker

KILDE: Forfatter af denne artikel: Egil Tveterås, Norsk biografisk leksikon. 2009. |

HANS THØGER WINTHER, A Norwegian Pioneer in Photography, by Robert Meyer

in honor of Dr. HEINZ K. HENISH editor of HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY on the occasion of his 65th birthday 1988. Kilde HER.

|

Little is known internationally about the Scandinavian history of photography, because few photohistorians have done research in this field and Scandinavian publishers have not found the field to be a research area worthy of their investment. Thus the Norwegian inventor of photography, Hans Thøger Winther, is hardly known outside of Scandinavia. Photohistorians Beaumont Newhall and Helmut Gernsheim do mention my research on Winther in their histories.1. The only other international presentation of Hans Thøger Winther is due to Wolfgang Baier 2, who relied in large part on the earlier research of the former archivist at the Science Museum in Oslo, the late Rolf A. Strøm, who wrote an interesting article on Winther in 1958.3.

A BRIEF BIOGRAPHY Hans Thøger Winther (l786-1851) was born in Thisted, Denmark, when Norway was still under Danish rule. At the age of fifteen, in 1801, he moved to Christiania (Oslo) with his parents. Here he was educated as a lawyer and by 1815 was appointed attorney-at-law for all of the Superior Courts of Norway. In 1814, Norway gained freedom from the four hundred years of Danish rule and entered the union with Sweden. As Winther had lived for so long in Christiania, had been educated in Norwav, and had family and career there at the time of liberation, he naturally became a Norwegian citizen and looked upon himself as entirely Norwegian. In 1822, he opened a bookshop with a music rental library, and early in 1823 he established the first lithographic press in Norway. Two years later, bookprinting was added to the enterprise. Music was his initial publishing interest, but he soon turned to pictures and smaller books. As the enterprise grew, one periodical after another came into being. In 1834, he started the first popular illustated magazine in Norway, Archiv for Læsning eller Norsk Penning-Magazine, after the popular international model. Because he had his own lithographic press, he did not need to depend on the numerous xylographic illustrations offered in stereotype by the large circulated magazines, such as The Penny-Magazine and Magazin Pittoresque. He had the advantage of superior reproduction quality, and could use original pictures of Norwegian origin. During his active period as editor (1822-1847), he became one of the dominant publishers in Norway. With a serious interest in the diffusion of knowledge, and his love for the Norwegian culture and history, he devoted his production to his concerns with the development of science, industry, arts and handicrafts, in addition to mythology and legends, history, poetry, and easy reading. When Daguerre's invention of photography was announced in the daily newspapers in 1839, Winther immediately understood the importance of the new art, and chronicled in his own magazines the events as they developed. Without a doubt, Hans Thøger Winther was the first in Scandinavia to make photographs and to claim to have made independent inventions in photography. In July 1839, he had drafted a document - his testimony affirmed by witnesses - sealed it in an envelope, and deposited it in the custody of a third party.4. Winther then awaited the publication of Daguerre's invention, as he truly believed that he had solved the secret of Daguerre's process. But the daguerreotype process turned out to be based on a different principle altogether. Instead of publishing his own results at that point, Winther continued his experiments. In May-July 1842, he advertised a book about his discoveries, but received little response. 5. Because he discovered a new process at the end of July 1842, he decided to postpone publication. He hoped to have the book out on the market before the Scandinavian Natural Scientific Meeting in Christiania in the summer of 1844, but he failed to meet that deadline. In the meantime, he published five of his own photographs to create more interest in his process of photography on paper. In 1844, he again advertised for book subscribers, and finally the book was released in May 1845. 6. The novelty had been lost, however. By that time, daguerreotypes were common, as the first daguerreotype studios had been open in Christiania for a couple of years. WINTHER'S HANDBOOK Hans Thøger Winther's 1845 book was the first handbook on photography on paper in Scandinavia. The book presents his own processes, which are entirely based upon his own research and inventions, and includes his own design for the constuction of a photographic camera outfit with interchangeable lenses. The book's full title was Anviisning til paa trende forskjellige Veie at frembringe og fastholde LYSBILEDER paa Papir, som Portraiter af levende Personer, Prospecter efter naturen, Copier af Malerier, plastiske Gjenstande, Kobbere, Steentryk, Blade af Planter &c, deels ved at benytte Cameraobscura, deels et til Copiering indrettet Instrument. En Opfindelse af H. T. Winther. Overrets-Procurator (Christiania 1845). Simultaneously, a Cerman edition was published: Anweisung auf drei vershiedenen Wege Lichtbilder...auf Papir hervorzubringen und festzuhalten (Christiania 1845). Today, Winter's book is a rare and highly original work on the subject of photography, with sixty-four pages and one lithographic plate. In an introductory chapter, he recounts the brief history of photography, from Davy, Wedgwood, Niépce, Daguerre, and Talbot, to Kobbel and Steinheil, and includes his own story. In the first chapter, he explains the camera equipment and refers to the plate illustration. In the following chapters, he explains the three photographic processes he developed during the period 1839-1842: the direct positive process; the paper negative/positive process; and the reversal process. The book includes a separate appendix that provides the chemical formulas. Originally, the appendix was seaIed in a separate envelope, and the book could not be returned for a refund if this envelope had been opened. The selling price was one Specie Daler. Daguerre's handbook had been translated and published earlier, in October 1839 in Denmark, 7 and in Sweden three months later, in December 1839, in the form of a small booklet. 8. WINTHER'S FIRST PROCESS To understand Winthes's contributions to the history of the medium, we need to see him in relation to other inventors of photography and compare his achievements with those that were written about in contemporary publicahons. Hans Thøger Winther was neither the sole nor even the first inventor of photography, but he did discover several original solutions to the basic problem of preserving the elusive image of the camera obscura. Winther's first method of making photographs was a direct positive process on paper, which through his writing in 1839 can be dated to June 1839. At this time, he could hardly have had knowledge of other inventors in the field. In 1839, both Jean Louis Lassaigne in France and Andrew Fyfe in Scotland discovered the same direct positive method and made their processes publicly known. In 1840, Sir John Herschel in England, and François Vérignon and Hippolyte Bayard in France, published similar processes. Later, even Dr. Alexander Petzhold (Dresden, Germany), Karl Emil Schafhäutl (Munich, Germany), Sir William Robert Grove (England), Alphonse Louis Poitevin (France) and others were doing the same. Winther had probably experimented further with Talbot's fixing agent of March 1839, described in "An Account of the Process Employed in Photogenic Drawing." 9. Here Talbot described the use of potassium iodide as a fixer. It seems as if Talbot himself had not yet observed the light-sensitive properties that the iodide fixer contributed through bleaching. The fixing method was due to an excess of silver iodide (or any other silver halide), which deprived the silver chloride of its light sensitivity. The iodide solution also functioned as a light-sensitive bleaching agent. The method was as simple as preparing a "photogenic" (sensitized) paper and exposing it to sun or daylight until it darkened with a blue-violet hue. It was then soaked in a weak solution of potassium iodide. When moist, the sensitized paper was quite light-sensitive, and would record even the faint image of the camera obscura of Talbot's day. Although Talbot's invention is best known to us today, several other people shared in the discovery of this principle, as we have seen, and most direct positive processes published resemble each other, even though Talbot included the method in his patent number 8842 (1841). From this we can assume that Winther not only followed the latest developments of the daguerreotype process but was aware of publications of other photographic processes as well. Winther took the process somewhat further than his competitors, however. Because the process depends on the liberation of iodine during the exposure to light, the starch that was found in most papers was discolored to blue, and this is actually used today as a test for the presence of starch. This discoloration attacked only the light areas of the image, and so discoloration destroyed the quality of the visual image, as white areas became dark blue. Rather than accept this shortcoming, Winther looked for a method of removing or reversing the effect. He found that magnesia alba (magnesium oxide) achieved the desired effect so that the iodine was removed, the starch regained its whiteness, and the image was cleared of the blue cast. WINTHER'S SECOND PROCESS Winther's second invention, the negative/positive process, resembles Talbot's calotype process, except that Winther did not use gallic acid. Instead, he found another, even stronger developer in the extracts of sumac. We should not be too eager to credit Talbot with the discovery of using organic reducing agents as developers. During the autumn of 1839, the chemist and medical doctor Alexander Petzhold of Dresden wrote that organic acids like gallic acid, tannin, and others actually reduced silver salts in a photogenic paper. His publication, "Über Daguerreotypie," is dated August 6, 1839. 10. Another article, "Petzhold's Methode Lichtzeichnungen Darzustellen," was published November 15, 1839, and referred to the same findings. 11. There are reasons to believe that these papers were widely read in European scientific circles. WINTHER'S THIRD PROCESS The third process is the most intereshng, as Winther was the sole discoverer of this peculiar reversal photographic process on paper. The method was developed late in June 1842, and the light sensitive material was potassium dichromate. After exposure, Winther reversed the image and developed a positive representation using silver chloride, thus bringing out the lights and shadows with a purple-bluish hue on the surface of the paper. The pictures were different from other photographs on paper, where the light areas are due to the white base of the paper. In Winther's images, the white areas are developed chemically. An anonymous person was shown the first results of the process early in August 1842 in Winther's bookshop. That witness wrote an article in a newspaper about his encounter: "The principle for one of these methods, the one he (Winther) just recently discovered, and in which he finds pleasure, is founded on a so far unknown chemical factum. The specimens of this process, which are on view, are all successfully done .... If Winther had lived in London, in Paris, or one of the major German cities, he would have had great success with his discovery." 12. The use of potassium dichromate was not new. The first photographic use of the chromium salt was proposed by the vice president of the Scottish Society of Arts, Mongo Ponton. 13. The French scientist Edmond Becquerel published another process, also based on Ponton's discovery. 14. Becquerel utilized the discoloration of starch by the iodine, ending up with a blue positive image. Robert Hunt, the eminent English chemist, published a process he named "Chromatype," though his process employed a different use of the chromium salt. Hunt's process was officially announced during the Cork Meeting of The British Association in August 1843, 15. and described in his manual, Researches on Light (1844). 16. Robert Hunt's "Chromatype" process was not published in Norway until 1845. 17. |

inther's only problem with this third process was the low sensitivity of the potassium dichromate. Accordingly, he wrote letters to the most notable scientists of his time in Scandinavia, including Professor Jøns Jacob Berzelis (Stockholm, 1779-l848), and Professor Hans Christian Ørsted (Copenhagen, 1777-1851), and to Professor Ludwig Ferdinand Moser (1805-1880) in Königsberg. In some of the letters, which have been preserved, he explained that he was looking for an agent or chemical compound that could increase the light sensitivity of the potassium dichromate. In his first letter to Berzelius, he wrote, "With the potassium dichromate I have developed especially beautiful renderings, and if it could be made sensitive enough for the camera obscura, one could make positive pictures on paper, that would not be inferior to the daguerreotype, that would be less expensive, and could be used with greater safety of operation, and that would have the peculiarity of producing pictures in many beautiful shades of colors, and thus a lot would be won for the Arts and Sciences." 18.

Winther postponed the publication of his book, so that he could improve his third process to make it a more workable photographic method, based on the same principles. None of the scientists with whom he corresponded seemed to have been of much help. At last, and many years too late, he finally printed the handbook. It was first advertised on May 4, 1845, in Christiania, and in other Scandinavian capitals, as well as in southern Germany. WINTHER'S PHOTOGRAPHS In 1826, Winther had built a camera obscura. His intention was to make a series of views for the lithographic press, though nothing came out of that project. Later, however, several series of Norwegian lithographic views were issued, by Winther and others. The camera obscura would give him an opportunity to get true representations of the views. During the summer of 1826, Winther recounts in his handbook (p. 7) that one of his children left in the camera obscura a small piece of paper impregnated with the juice of berries. During a three-month exposure with bright sunlight, the faint image of his white garden house became visible on the paper, due to bleaching. When he learned about Daguerre's invention in February 1839, he remembered the incident of 1826, and in the hope of solving Daguerre's secret he began his own experimentation with the juices of fruits, extracts of litmus, and silver salts. Most of his experiments employed contact prints in the traditional way, with leaves and pieces of lace. As he managed to control and improve the process, he acquired better equipment. In his letters to Berzelius, he also refers to his "Voigtlanderske" instrument, which probably refers to the optics. Because he needed a camera with special functions for moist paper photography, he constructed his own practical wooden camera. But he probably bought the best lenses he could find, lenses with the largest lens opening and the highest definition that he knew of: Voigtlander. I believe that all his known camera images were taken with these lenses; the formats do not change. While experimenting and researching the photographic processes, Hans Thøger Winther exhibited the results in the book store, for everybody to see. He also advertised these exhibitions in the newspapers. From 1842 on, he published some of the photographs in his own magazines, using hand-worked lithographs for reproductions. The five different views that were issued are all we have left of Winther's own camera photographs, as far as I know. The motifs are street scenes and new buildings in Christiania of the day (1842): 1) "Prospekt af Bankbygningen i Christiania" ("View of the Bank Building in Christiania"), published September 1, 1842; 2) "Frimurerlogen i Christiania" ("The Freemasonry Temple in Christiania"), published February 21, 1843; 3) "Grunnings Løkke ved Christiania" ("Crunning's Carden near Christiania"), published April 8, 1843; 4) "Kongens Gade i Christiania" ("The Kings Street in Christiania"), published May 10, 1843; 5) "Slottet ved Christiania" ("The Royal Castle near Christiania"), published June 1, 1843. The choice of topics fits perfectly his original idea of publishing typical Norwegian views, so we can easily place the interest in photography in the same context as the production of views. In his subscription notice for the book, he stated, "I am convinced that my invention and method will be useful for Art and Science.... The travelling scientist can, without prior knowledge of drawing, enrich his portfolio with views, monuments of the past, objects of natural history, etc. The landscape painter may, in a couple of minutes, record the view he wants to paint, with all its details, and with an absolute correctness of perspective, and avoid the troublesome drawing, especially of many unneccessary objects that, nevertheless are of importance and give painting greater truth." 19. AFTER 1845 Hans Thøger Winther's photographic endeavours did not bring much advancement to the photography in Scandinavia. The processes were never used for professional purposes, as far as I know, though he did encourage amateur photography in 1845. A young farmer's son, Amund Larsen Gulden, from Hadeland, a Norwegian land-district, became interested in Winther's photography on paper and worked with his processes for some time in 1845-46. He even bought a cheap, model of the Winther camera, made of cardbord by one of the bookbinders in Christiania. 20. Winther himself quit photography and continued to pursue other inventions. In 1846, he had invented eyedrops that enabled people to see better in the dark winter evenings, candels that gave more light and a new sort of black ink, that could be seen immediatly as it was used for handwriting. 21. All of these inventions came out of pure necessity, as the sixty-one-year-old Hans Thøger Winther probably was loosing his eyesight. In 1847, Winther let others take over his printing press and workshop, and he retired from publishing. There is nothing left from Hans Thøger Winther's photographic activity, apart from the published materials and his letters. After his death in 1851, the family seems to have gotten rid of everything. The same year, they held a book book auction, and Winther's rich holdings of books, including much of his private library, were sold. Winther's last traces were swept away when his daugther and son-in-law tore down his old house and built a grand new house on the same property. Notes: 1. Beaumont Newhall, The History of Photography from 1839 to the present, New York (1982), p. 25. Helmut Gernsheim, Le origina della fotografia, Milano (1981), p. 219-21, note 5, p. 252 Helmut Gernsheim, The Origins of Photography, London (1982), p. 235-7, note 5, p. 272 Helmut Gernsheim, Geschichte der photographie, die ersten hundert jahre, Frankfurt am Main (1983), p. 188, ref. 4, p. 744. 2. Wolfgang Baier, Quellendarstellung zur Geschichte der fotografie, Leipzig (1966), p. 110ff., 114, 335. 3. Rolf A. Strøm, Hans Thøger Winther, Volund 1958, Norsk Teknisk Museum, Oslo (1958), p. 138-158 4. H.T.Winther, Anviisning til paa trende forskjellige Veie at frembringe og fastholde LYSBILLEDER paa Papir, Christiania (1845), p. 12. 5. Morgenbladet, Christiania, nr. 150, (05/30/1842), p. 2. H.T. Winther, Kunsten at fastholde Lysbilleder. Norsk Penning-Magazin, Christiania (1842), vol. 9, nr. 7, sp. 219-22. 6. Morgenbladet, Christiania, nr. 154, (06/02/1844), p. 3. 7. J-L-M. Daguerre, Praktisk Beskrivelse af Fremgangsmaaden med Daguerreotypen og Dioramaet af Daguerre, Nyt Magazin for Kunstnere og Haandverkere, Copenhagen, (1839),No. 15, Oct. 31., p. 126-128, and No. 16-17, Nov. 7., p. 129-148 + 1 lithograph. Facsimile reprint: Norsk Fotohistorisk Journal, Oslo (1976), vol. 1, nr. 4, p. 69-96. 8. Aftonbladet, Stockholm, (12/23/1839). 9. An Account of the Process employed in Photogenic Drawing, in a Letter to Samuel Christie, Esq., Sec. R.S., from H. Talbot, Esq., F.R.S., London and Edinburgh Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, (March 1839), p. 209-211. (Read before the Royal Society, 02/21/1839). 10. Dr. Alexander Petzhold, Uber Daguerreotypie, (dated 08/06/1839) Journal fur praktische Chemie, von Erdmann und Marchand, Leipzig (1839), Vol. XVIII/1-2, p. 111-12. 11. Petzhold's Methode Lichtzeichnungen darzustellen, Dinglers Polytechnisches Journal, Stuttgart, Vol. 74/4, p. 316., (Published 11/15/1839). (Refering to Erdmann und Marchand's Journal). 12. Anonymous, Kunsten at fastholde de i camera obscura dannede Lysbilleder paa Papiir, Den Constitutionelle, nr. 219, (08/07/1842), p. 3. 13. Mungo Ponton, Notice of a cheap and simple method of preparing Paper for Photogenic Drawing,in which the use of any salt of silver is dispenced with, The New Edinburgh Philosophical Journal, Edinburgh, (July 1839), p. 169-171. 14. Edmond Becquerel, Note sur un papier impressionnable a la lumiere, destine a reproduire les dessins et les gravures, Comptes Rendus des seances de l'Academie des Sciences, Paris, Seance du lundi 16 Mars (1840), p. 469-471. See also: Edmond Becquerel, Ueber ein fur das Licht empfindliches Papier zum Copiren von Zeichnungen und Kupferstichen, Dinglers Polytechnisches Journal, Stuttgart (1840), Vol. 76/4, p. 301-303. 15. Robert Hunt, On Chromatype, a new Photographic Process, Notices and Abstracts of Communications to The British Association for the advancement of Science at the Cork Meeting, (August 1843), p. 34-35. 16. Robert Hunt, Researches on Light, London (1844), p. 150-51. 17. Anonymous, Papir til Lysbilleder, Skilling-Magazin, nr. 20, (05/17/1845), p.160. 18. H.T. Winther's letter to Jøns Jacob Berzelius, (dated 11/26/1843) (The Royal Library, Stockholm). 19. H.T. Winther, Kunsten at fastholde Lysbilleder, Norsk Penning-Magazin, Christiania (September 1842), vol. 9, nr. 7, sp. 221. 20. R. Meyer, Amund Larsen Gulden - Norges første fotograf, Hadeland, (05/30/1981), p. 5. R. Meyer, Norges første amatørfotograf, Aftenposten, (06/26/1981), p. 5. 21. H.T. Winther, Godt og paalideligt sort Blæk, Morgenbladet, nr. 87, (03/28/1846), p. 1-2 Anonymous, Hr. Overretsprokurator H.T. Winthers sort-af-pennen-flydende Blæk, Morgenbladet, nr. 112, (04/21/1846), p. 2-3. |